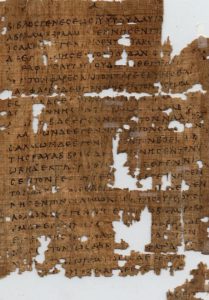

Fragment of the Gospel According to Matthew (original autograph: ~60-70 A.D.); This is a copy dating to ~250 A.D. (Wikimedia Commons)

In a 2013 article entitled, Is the New Testament Text Reliable?, Greg Koukl tacked the old assertion that the New Testament has been copied and recopied so many times over the ages that today, we can’t even know what the original texts said. To kick off that article, Koukl used a great example of how this meme continues to be perpetuated:

In the spring of 1989 syndicated talk show host Larry King interviewed Shirley MacLaine on the New Age. When a Christian caller contested her view with an appeal to the New Testament, MacLaine brushed him off with the objection that the Bible has been changed and translated so many times over the last 2000 years that it’s impossible to have any confidence in its accuracy. King was quick to endorse her “facts.” “Everyone knows that,” he grunted.

Unfortunately, it’s not just entertainers like King and MacLaine that repeat such memes. Sometimes, respected academics do it, too. Consider this from scholar Bart Ehrman, as he describes the number of textual variations that exist among our approximately 5,800 known Greek New Testament manuscripts:

Scholars differ significantly in their estimates—some say there are 200,000 textual variations known, some say 300,000, some say 400,000 or more! We do not know for sure because, despite impressive developments in computer technology, no one has yet been able to count them all…There are more variations among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament.1

Many scholars have written books and articles thoroughly investigating—and eviscerating—the assertions repeated by King, MacLaine, Ehrman, and others. We’ve shared some of the key points in other articles here and here. Those points can be summarized as follows:

- Critics often liken the transmission of biblical texts to a child’s game of “telephone” in order to illustrate how errors and variations can develop. This analogy is inappropriate for a couple of reasons. First, “telephone” represents an oral transmission of information, not written. Second, it assumes a linear transmission of data, as if one copy was made, then a second copy was made from the first, then a third copy from the second, a fourth from the third, etc. That, too is incorrect. In reality, master copies were often used for long periods of time to produce many, many other copies. For example, the fourth century Codex Vaticanus was re-inked in the 10th century, indicating that it was being used for at least 600 years. Some books could have been used to make copies for centuries, further protecting the integrity of the text.2 So, the New Testament texts were transmitted somewhat “geometrically” rather than via a purely linear process.

- There are so many variations simply because we have so many existing manuscripts (about 5,800 in Greek, the text’s original language3). This is actually a “good problem” to have.

- The bulk of those texts date from the second millennium A.D., but some examples go all the way back to the 2nd century (and perhaps even the first century).4 Therefore, our earliest copies are very close in time to the originals (mere decades). Compare that to centuries (from creation of the assumed original to the first surviving copies) for other documents from antiquity, and the New Testament texts look quite good.5

- The surviving New Testament manuscript evidence is extremely robust. It not only goes back much further, but also offers far more texts than any other documents we have from that period of antiquity.

- The great number of texts enables scholars to cross-check copies and determine, with a very high degree of confidence, what the original texts said.

- Of all the variations (whether 200,000 or 400,000, or more), the vast bulk are small spelling variations, slight word order changes, and the like, and none impact basic Christian doctrine.6

The fact is, critics are vastly misrepresenting the truth when they assert that textual transmission happened like a “game of telephone” and that 400,000+ variations across a document with 138,000 words means that the original wording cannot be reliably determined.

Simply put, the critics are wrong. The large number of variations is a by-product of the phenomenal number of surviving Greek manuscripts. Scholars have an “embarrassment of riches” when it comes to these manuscripts, and they absolutely can determine that they have been transmitted to us reliably. We can, and have, recovered the vast bulk of the original wording (significantly better than 99%) with a high degree of confidence.7, 8

Now, none of this speaks to whether those original words provide accurate historical accounts. There’s ample evidence that they do, but that’s a different topic, covered by a wide range of other resources, including this website.

Notes

- Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why, Harper San Francisco, 2005, p.89

- Craig L. Blomberg, Can We Still Believe the Bible?: An Evangelical Engagement with Contemporary Questions, Brazos Press, Grand Rapids, MI, 2014, p. 34

- Justin Taylor, “An Interview with Daniel B. Wallace on the New Testament Manuscripts”, The Gospel Coalition blog, March 21, 2012, accessed January 10, 2015 at http://blogs.thegospelcoalition.org/justintaylor/2012/03/21/an-interview-with-daniel-b-wallace-on-the-new-testament-manuscripts/

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Blomberg, p. 27-28, also including a citation of Bart Ehrman stating the same fact in the appendix to the paperback version of Misquoting Jesus

- Greg Koukl, “Is the New Testament Text Reliable?”, Stand to Reason blog, Feb. 4, 2013 (citing work by Geisler and Nix, A General Introduction to the Bible, Chicago: Moody Press, 1986, p. 475), accessed January 10, 2016 at http://www.str.org/articles/is-the-new-testament-text-reliable#.VpLUCvkrLIV

- John W. Wenham, Christ and the Bible, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, MI, 1984, pp. 186–87