Easter is just around the corner, that time each year when Christians celebrate the death and resurrection of Jesus. Christians believe that Jesus was God in the flesh, who came to earth and allowed himself to be sacrificed for the sins of each human being, paying the wages of sin on our behalf. Three days later, the teaching goes, Jesus overcame death via the resurrection and, through Him, provides each one of us a path to eternal life.

It makes for an interesting—and quite incredible—story. Skeptics down through the ages have attempted to disprove it, directing their fire at the key pieces of the story: 1.) Jesus’ death by crucifixion; 2.) His burial in a tomb; and 3.) Various elements related to the resurrection itself.

Despite all this, Jesus’ story remains remarkably compelling. Is it because it’s a hopeful one for all humanity? Partially. But it’s also because there’s an incredibly strong historical case for the truth of it all. Let’s take a look.

Death by Crucifixion

Crucifixion was a tortuous means of execution employed by the Romans, and it was typically reserved for lower-class criminals, traitors, and others that the Roman authorities deemed undesirable. Death by crucifixion was considered a disgrace and a curse by Jewish people at the time.

The fact that Jesus died by crucifixion is extremely well attested historically. All four canonical gospels relate the crucifixion story. In addition, the first century Jewish historian, Josephus, writes about the crucifixion in The Antiquities (18:63-64), saying, “When Pilate, upon hearing him accused by men of the highest standing among us, had condemned him to be crucified, those who had in the first place come to love him did not give up their affection for him.”

Tacitus, the first century Roman historian, also writes in his Annals (15:44), “Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus.”

Other non-Christian writers also mention the crucifixion. One of whom is Lucian, the 2nd century Greek satirist. In The Death of Peregrinus, he writes, “The Christians, you know, worship a man to this day—the distinguished person who introduced their novel rites, and was crucified on that account.”

Considering that death by crucifixion was considered such a disgrace, it’s highly unlikely that followers of Jesus would invent the notion that he died in that manner. The truth is, Jesus was executed by crucifixion. The large majority of reputable scholars today—Christian and skeptic—accept this fact.

Burial in a Tomb

One assertion made by anti-Christian authors, such as Bart Ehrman in his recent book, How Jesus Became God, is that Jesus was never buried in a tomb. Contrary to gospel accounts, they say, the Roman authorities did not allow executed criminals to be buried. There was no “empty tomb” from which the resurrected Jesus could have emerged because there was no tomb at all.

Instead, Ehrman asserts, the idea that Jesus was buried in a tomb was a late fiction, invented by supportive Christians and woven into Jesus mythology. The trouble is, the historical and archeological evidence makes a compelling case for the truth of the gospel accounts.

Craig A. Evans, of Acadia University in Nova Scotia, addresses the issue in his essay, Getting the Burial Traditions and Evidences Right, which comprises chapter 4 of the book, How God Became Jesus.

Of Ehrman, Evans says, “His description of Roman policy relating to crucifixion and non-burial is unnuanced and incomplete, especially as it relates to policy and practice in Israel at the time of Jesus.” (p.73). Roman law did, in fact, allow for the bodies of executed criminals to be released for burial. Evans cites a passage from book 48 of the Digesta, a summary of Roman law, which says:

The bodies of those who are condemned to death should not be refused their relatives; and the Divine Augustus, in the Tenth Book of his Life, said that this rule had been observed. At present, the bodies of those who have been punished are only buried when this has been requested and permission granted; and sometimes it is not permitted, especially where persons have been convicted of high treason. Even the bodies of those who have been sentenced to be burned can be claimed, in order that their bones and ashes, after having been collected, may be buried. (48.24.1)

The bodies of those who have been punished should be given to whoever requests them for the purpose of burial. (48.24.3)

It is true that Roman authorities did sometimes deny requests, and leave bodies exposed as examples to others. However, significant evidence exists that the Roman authorities in Israel actually respected Jewish law and tradition (related to burial and other issues), particularly in peace time. Both Philo and Josephus, who were alive during the mid-first century, indicate that Roman authorities in Israel acquiesced to Jewish traditions and laws. This was especially true regarding burial traditions, which were highly important to first century Jews.

So what did Jewish law require regarding the burial of criminals? It specified the following regarding burial:

If someone guilty of a capital offense is put to death and their body is exposed on a pole, you must not leave the body hanging on the pole overnight. Be sure to bury it that same day, because anyone who is hung on a pole is under God’s curse. You must not desecrate the land the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance. (Deuteronomy 21:22-23, NIV)

It’s clear that Jewish law required the executed to be buried by nightfall, if possible, otherwise the land would be “desecrated.” Roman authorities would have respected these laws during peace time. Therefore, it is likely that Jesus’ body would have been released for burial.

It’s also important to remember that Jesus was executed under Roman authority, but had been handed over to the Romans by the Jewish Council, who asked that the Romans put him to death. According to Jewish law at the time, the Jewish Council (Sanhedrin) would have been responsible for ensuring the burial of persons they had condemned. After all, it was their responsibility to ensure that the land was not defiled.

Therefore, the gospel account saying that Joseph of Arimathea (a member of the Sanhedrin) made a formal request to the Roman governor for Jesus’ body—and provided a tomb for his use—would have been entirely consistent with Jewish law and practice. The Romans’ release of Jesus’ body would have also been consistent with Roman law and practice at the time.

In 1968, archeological evidence surfaced reinforcing the notion that crucified people were allowed to be buried. An ossuary was recovered containing the bones of a Jewish man named Jehohanan. Analysis indicated that the man had been crucified. Most telling was that a large nail was still embedded in his heel.

Simply put, the evidence indicates that Roman authorities did respect Jewish tradition and law, and allowed executed criminals to be buried during peace time. The gospel accounts of Jesus’ death and burial are well-supported.

The Empty Tomb

Following Jesus’ crucifixion, his body was sealed in a stone tomb. A heavy stone was placed in front of the tomb’s opening, and guards placed at the entrance (at the request of Jewish authorities).

Several days later, when a couple of women went to the tomb to anoint the body, they found the tomb open, unguarded, and empty. According to the gospel accounts, an angel told the women that Jesus had risen. The women then left and excitedly informed the disciples. In subsequent days, the risen Jesus appeared to the disciples, as well as to hundreds of other people. From that point, the disciples began their mission to spread the Christian message.

The empty tomb is a core element of the story, and three basic arguments support its reality. First is what New Testament scholars Gary Habermas and Mike Licona in The Case for the Resurrection of Jesus call the “Jerusalem Factor.” Jesus was very publicly crucified in Jerusalem. He was buried there, and that is where he allegedly arose from the dead and made numerous appearances. Neither the Jewish nor the Roman authorities in Jerusalem wanted the nascent Christian movement to continue. If Jesus’ body had been in the tomb, then Christianity would never have gotten off the ground. As history has shown, Christianity did get off the ground and spread rapidly.

No Roman or Jewish officials ever surfaced to claim that the body had been found, nor did anyone ever display a body in an attempt to quell the talk of Jesus’ resurrection. Why? Because there was no corpse to display.

Related to this is another argument in favor of the empty tomb: Enemy attestation. None of the earliest critics of Christianity—including those present at the time—argued that the body was still in the tomb. Instead, they argued that Jesus’ disciples must have stolen the body and hidden it (e.g., Matthew 28:13; Justin Martyr, Dialogue With Trypho, 108). The empty tomb was, even to the critics, a fact that had to be explained. It was not a myth to be denied. The argument that the disciples stole the body and then preached the Christian message for the rest of their lives as a lie does not make logical sense. Why would these disciples have devoted their lives—and then died as martyrs—for something they knew to be false? The short answer is they didn’t.

The third argument relates to the testimony of women. In ancient Jewish society, as well as in Roman society, women were considered to be second-class citizens and their rights were very limited. In addition, their testimony in court was basically considered useless.

Given the nature of society at the time, it is highly unlikely that gospel authors would have invented a story in which the first witnesses to the risen Christ were women, who then went and informed the men. This would actually have served, in many people’s eyes at the time, to harm the story’s credibility! If the story had been invented, then the authors would almost certainly have written that men were the first witnesses. The only reason to write the “embarrassing” fact that women discovered the empty tomb, is that it was true.

Disciples’ Belief in Experiences with the Risen Jesus

Following Jesus’ crucifixion (but before the resurrection), the disciples were frightened, demoralized, and basically in hiding, fearing that they might be next. Then, after their reported experiences with the risen Jesus, they pulled a complete 180-degree turn. As instructed, they went out and began to preach the gospel publicly, at great personal risk and for no gain. Nearly all were ultimately killed for their beliefs, and none ever recanted, even when facing torture and death.

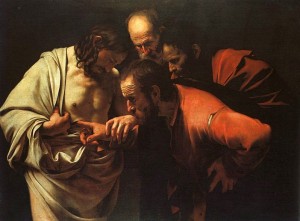

Plenty of people will die for something they believe to be true. However, nobody wants to die for something they know to be false. As self-described eyewitnesses to the resurrected Christ, the disciples were in a position to know for sure the truth of their claims. They were there, and honestly believed that they had seen, touched, eaten with, and spoken with the resurrected Jesus.

This experience impacted the disciples greatly. Their own actions after the event are strong enough testimony. However, there are others who also testify to that fact. Several of the early church fathers, who interacted with and then succeeded the original apostles, personally witnessed these impacts and wrote about the disciples’ certainty of what they had seen. These include Clement of Rome (c. 30-c.100) and Polycarp, who was martyred at 86 years of age around the year 160 A.D.

Ignatius, a colleague of Polycarp, who was martyred himself in Rome around 107 A.D., wrote in his letter to the Smyrnaeans that the disciples, after seeing the risen Jesus, were so moved and encouraged that they “disregarded death.”

Tertullian, writing around 200 A.D. in Scorpiace (Chapter 15), records the deaths of Peter and Paul, and adds that if anyone doubts the Christian accounts of some of the disciples’ deaths, then they could check the public records. That statement indicates that such records were extant at the time and open to scrutiny.

Origen, a later church father (c.185-c.254), wrote in Against Celsus that the disciples’ devotion to Jesus “was attended with danger to human life” but that they “were first to manifest their disregard for its (death’s) terrors.”

Belief in the resurrection came about immediately after the event. Jesus disciples’ experienced something overwhelming that transformed them from frightened and demoralized people into dedicated evangelists who devoted their lives to sharing the gospel. All but one (John) died as martyrs for their beliefs, and John endured torture and exile. Critics’ explanations that the disciples stole the body, or that Jesus somehow survived the crucifixion (the “swoon theory”), or that the disciples experienced multiple mass hallucinations, all fall apart under scrutiny, leaving the resurrection as actually more believable.

Paul’s and James’ Conversions

The figure of Paul is central to Christian history. His missionary work throughout the Roman Empire was critical in spreading Christianity throughout the Gentile (non-Jewish) population. However, Paul was not always a friend of Christianity. Originally called Saul of Tarsus, he was a Pharisee and an avowed enemy of the fledgling Christian church. He actively worked to identify and help persecute Christians.

Things abruptly changed sometime between 31 and 36 A.D. While travelling to Damascus, Saul had a stunning encounter with the risen Jesus. As a result of this experience, he changed his name to Paul and began a long and dangerous mission to help spread the Christian message to the Gentiles. In the early to mid 60’s A.D., Paul was killed for his actions, executed under authority of the Roman Emperor, Nero.

The story of James, brother of Jesus, can be pieced together from both Christian and non-Christian sources. By all accounts, James was a pious Jew who did not follow Jesus during his earthly ministry. In fact, he was skeptical of Jesus claims, and remained so until after Jesus was crucified.

After the crucifixion, James was allegedly visited by the risen Jesus. That experience had quite an impact on James, and he became a committed Christian. In fact, he later assumed a leadership position in the church in Jerusalem. Sometime in the mid-60’s A.D., he was killed for his role in spreading Christian beliefs.

It would be easy to dismiss the story of James as “Christian propaganda” if it weren’t so well attested in multiple sources. Even sources that today reside in the Bible must be taken seriously because, it must be remembered, they were never originally intended to be collected in a holy book. They are books and letters written by different people at different times for different purposes, and were only later collected into a biblical canon. Yet, they corroborate one another. These sources include the gospels of Mark and John; an ancient oral creed, cited by Paul in his first letter to the Corinthian church; Acts of the Apostles; and Paul’s letter to the Galatian church. Finally, multiple sources attest to James’ martyrdom: The Jewish historian Josephus (c. 37 – c. 100 A.D.), as well as the ancient historians Hegesippus (c. 110 – c. 180 A.D.) and Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215 A.D.), as quoted by a later historian, Eusebius (c. 260 – c. 340 A.D.)

The conversions of Paul and James aren’t just stories, they’re history. The question is: If these men were not visited by the risen Jesus, as the claims indicate, then what caused them to make such fundamental transformations?

A Final Thought

Jesus’ resurrection is the core of the Christian faith. Without it, there is no such thing as Christianity. The story of the resurrection has been subjected to intense scrutiny and criticism for nearly two millennia, yet it still stands, utterly unique, and with a strong historical case to support it. For those who want to learn more about it and the history behind it, there are numerous resources available, including works by Craig Blomberg, Gary Habermas, Mike Licona, Josh McDowell, Lee Strobel, N.T. Wright, and others. As always, it’s also worth reading the gospel accounts themselves. It’s a story that just might change your life.